A continuing complaint facing those involved in long-term infrastructure planning is the argument that it is impossible to forecast the future at all accurately. Adjustments to business case rules to counter ‘optimism bias’ were written into Treasury rules some 15 years ago. But scepticism runs deep.

One response is to point to experience. To those who doubt the likelihood that there will be continuing demand growth for HS2 to accommodate, the experience of the Virgin West Coast Trains’ franchise is relevant. The forecast made at the outset of this franchise in 1997 was for an unprecedented tripling of passenger numbers over the 15-year term of the contract. Some of the forecast growth was attributed to the planned transformation in level of service, with 20% journey time cuts and doubling of service frequencies. And the outcome? The 2012 forecast was not achieved until 2013: a remarkably robust outcome given intervening events – delays with the planned infrastructure upgrade; operations restricted to 125 mile/h rather than 140 mile/h; the global financial collapse and the recession that followed it…

“But the past is no guide to the future” it will be said. Simply extrapolating past trends would clearly be a hopeless way to proceed. Especially when there are macro-level shifts in the economy afoot. Here we set out what can be done to address the inescapable uncertainty in demand forecasting.

Did Network Rail see it coming?

Five years ago, Network Rail applied the idea of scenario planning to develop its long term planning forecasts. This work foresaw some major factors that might come to have an important bearing on the UK economy and hence on the demand for rail travel, including for the longer distance market.

The report suggested that:

“The economy can either be integrated with other national economies, trading regularly across all types of goods and services, or be isolated, producing all or most of its goods and services domestically.”

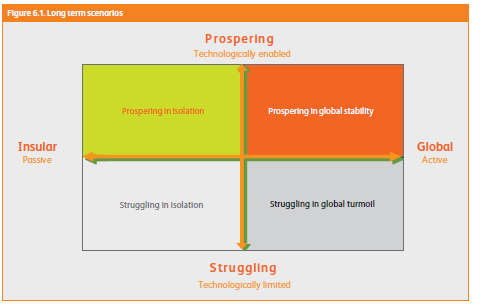

This was taken to imply four candidate long term outcomes for the Great Britain’s economy in Network Rail’s scenario analysis:

- Strong, global. A strong economy on the global stage which prospers from its integration with the rest of the world

- Strong, insular. A strong economy on the global stage which prospers from its self-sufficient nature

- Mid-ranking, global. A mid ranking economy on the global stage which suffers from its integration and trading position with other national economies

- Mid-ranking, insular. A mid ranking economy on the global stage which suffers from an absence of trade with other countries.

Network Rail saw a further major factor being how engaged the nation was in embracing technological innovation – as the following diagram shows:

With a prospering economy, Network Rail envisaged national income growth at close to its long term trend rate at 2.25% per annum.

But in the cases where the economy struggles, national income growth was expected to be much lower (0.5% per annum – actually a little above the overall performance since 2008, but much less than the 2016 outcome of 1.8%). Struggling in isolation was characterised by an “absence of both an export market for its high value products and a source of inexpensive [imports]” and [the nation] taking “little interest in solving social and environmental problems as it has neither the wealth [n]or technology to achieve this without worsening individuals’ standard of living”.

Struggling in global turmoil was little better: “….as the global supply chain and credit markets are volatile and other countries improve their employee skill levels and resource base”. But Britain takes “… an active role in addressing social and environmental problems…”.

The scenarios were applied to a set of major long distance flows to show their effect on long term demand forecasts. So taking London – Leeds, for instance, the four projections for base level demand change (that is ignoring supply side changes such as HS2) from 2012 to 2043 matching the four scenarios shown above were:

These are huge variations. And who knows which of the four scenarios best fits the current much-changed circumstances affecting the outlook for the UK economy. Note how progress on social and environmental policy was seen as having a bearing on outcomes as well as overall economic factors. The point about technological take-up would also no doubt have an impact on productivity – an area where the UK has fallen further behind over the last few years.

Repeated today, the scenarios would no doubt be re-specified in a number of key areas. But Network Rail deserves credit for thinking ‘out of the box’.

It would have seemed plausible to believe in a ‘prospering in global stability’ (PGS) in 2007, but it seems less probable as of 2017, certainly in the immediate and medium term. ‘Prospering in isolation’ or ‘struggling’’ might be a popular current prognosis and that would show demand forecast growth for London – Leeds in 2043 down by between a third and two thirds on the PGS level. And London – Leeds is by no means unusual as a selected city pair. Who said there was little risk transfer in bidding for rail franchises?

Understanding the drivers of travel demand

While considering the impact of macro-level changes, there are some stabilising factors that strongly influence the demand for long distance rail travel come what may. These include:

- the effect of fuel (oil) prices. These have risen dramatically in the last three months, and strongly influence demand for car and short haul flights because energy costs of these modes represent a much higher proportion of total costs than for rail. Moreover, as fossil fuel sources either dwindle (or become more expensive to use as a result of climate change policy), this effect will become more significant in future.

- rail’s competing modes are based on motorway and runway capacities that are effectively fixed over the next ten years or more, and neither mode is well placed to accommodate more demand. This has the effect of strongly magnifying the effect on rail of the demand increase that the economy generates

- the dominance of cities in driving jobs and economic growth, and the associated lifestyle choices that include a reluctance to bother with car ownership and a new generation at ease with rail travel as the best choice for travel over distance. London’s population has grown at twice the national rate over the last 5 years.

Indeed, these are probably three of the factors that saw long distance (and commuter) rail demand grow so strongly through the recession and ensuing slow-down over the last nine years. Last month petrol prices grew 16.8% year-on-year, the fastest growth rate since 2011. Scenarios are all well and good, but the overall message is that rail growth has proved to be very resilient in the past. The stabilisers have smoothed the way through the shifts created by wider economic factors.

Conclusion

Are the high levels of variation between the various scenario-based projections a reason to stall investment in projects such as HS2? We would say no. With Phase 1 parliamentary powers now secured with a strong political consensus, it is time to proceed to implementation and to progress the further stages of the high-speed programme, broadening its value to serve the whole country.

When it comes to investment appraisals and business cases, it is right to use scenarios or probabilistic devices (as used in the DfT projections of the economic case for HS2 since 2013) because there are major macro-economic factors in play that cannot be ignored. But there is always uncertainty, and as we have shown, rail’s position remains strong. More local effects are driving rail demand inexorably upwards. And the nation needs to invest in infrastructure to fulfil its economic potential.