At a Greengauge 21 seminar at the University of Plymouth on February 28th, we explored with key local stakeholders how a fully integrated public transport network could be developed for the South West. With some exciting rail developments taking place in Cornwall and Devon, three impediments to the progress all stakeholders are seeking emerged:

- The Cornwall integrated bus-rail service and ticketing plan – which has made huge progress – may not be able to achieve its aim of a truly integrated fares system. The reason? Interfacing a simplified local fares system across a diverse set of bus operators is feasible, but so far, incorporating rail fares, with all of the complexities of the national system, is proving a stumbling block

- Regional connectivity by rail is fragile. A month ago, £80m was committed to raising the height of the sea wall at Dawlish (5 years after the major breach which led to the line being closed for two months). While largely welcomed locally, this is only the first part of the necessary measures. The full programme of remedial measures will not be complete – on current performance – until 2030 or later. The programme will be expensive, probably disruptive, and even then, the risks of weather and climate change disruption, while reduced, will remain. All agree that works on the existing line via Dawlish and Teignmouth must be progressed because of the the instability of the cliffs and the inevitability of sea level rises causing increased problems (along the sea wall and also along the Teign and Exe estuaries). But these actions are not enough to ensure the resilience of the South West’s rail network. At our seminar there was wide agreement that the solution needed – in addition to the programme of works on the existing main line – is the re-instatement of the second main line via Okehampton and Tavistock: the challenge will be to persuade Ministers, DfT and Network Rail

- Local priorities are to get better rail services into Exeter and Plymouth – both expanding cities. But incremental local service development (Exeter-Okehampton and Bere Alston-Tavistock) may in practice impede the creation of the much needed second main line across Devon without a commitment and plan from the outset to full route re-instatement.

The solution to fares simplification and bus-rail integration may yet be found through negotiation with the rail franchisees and the Department for Transport. Possibly, the radical fares reform being considered in the Williams Review might prove a way forward. Indeed, the Cornwall (+Plymouth) integrated bus-rail network fares proposal could serve as a useful early test application of a radical change to national rail fares – extended to include connecting bus services – designed to restore public trust.

Re-instating the second main line via Okehampton and Tavistock

The need for a second main line across Devon – restoring a connection closed 50 years ago the formation of which (including all its major bridges) remains intact – is palpable. It stems from the now incontrovertible evidence of the effects of sea level increases. IK Brunel was a great engineer, but he could not have foreseen the problem of climate change.

South Devon and Cornwall remain at risk of being cut off from the rest of Britain. Yes, the line via Dawlish and Teignmouth must be better protected from the storm/high tides/sea level rise combinations that threaten it. But here is the one place in the UK where climate change risks cutting off a substantial part of the country. No research has yet been carried out to establish by how much the probability of breaches to the railway line and its services can be mitigated by line-of-route sea-defences.

So, what is inhibiting the restoration of the second main line? Three things:

- A belief that the northern route would result in slower journey times than the existing line, and so lead to a downgrade in connectivity

- Wishful thinking that presumes that work on the Dawlish-Teignmouth coastal route will alone ensure the resilience of the South West’s rail network – in practice there will be decades of work, a lot of disruption and continuing uncertainty as to outcomes

- The ambitions to re-open branch-line services at either end of the inland mainline rather than re-open the whole route.

We believe there are good answers to these three challenges.

Achieving comparable journey times via Okehampton-Tavistock and via Newton Abbot (the coastal route)

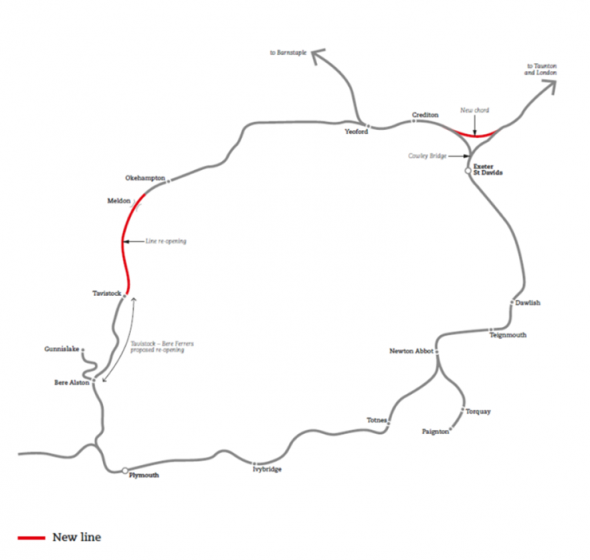

Greengauge 21’s report Beyond HS2 featured the re-opening of the second main line via Okehampton and Tavistock. An additional chord line was shown as being a candidate way to increase operating flexibility and to make possible similar journey times between Cornwall/Plymouth and the rest of the country via the two routes, north and south of Dartmoor. The overall concept is illustrated below:

Ensuring the resilience of the South West’s rail network

The chord line shown would allow trains to avoid the flood-prone Cowley Bridge area, as well as the need for reversal at Exeter to use the Okehampton Line. With plans to provide two trains an hour Paddington-Exeter (one fast, the other to make more intermediate station calls), it would make sense for the faster train for Cornwall to proceed as now via Network Abbot (divertible when the coastal route is closed) and the second train, instead of terminating at Exeter, going directly to Crediton, Okehampton, Tavistock and Plymouth. Alternatively, an equivalent arrangement could be adopted for Cross Country services. The re-stated line north of Dartmoor can be re-instated to support intercity line speeds, broadly equivalent to those feasible on the route south of Dartmoor (coastal line).

Network Resilience

It would be unwise to presume that Dawlish line works will solve the problem of network resilience. Studies of the effects of sea level rises (and cliff instability) show that virtually the whole route from the outskirts of Exeter to Newton Abbot would need protective works. Some of the route is inaccessible by road and it can be foreseen that the engineering work will entail either challenging and costly access by sea or disruption to the railway line, with for example extended periods of single-line working.

It would make good sense to prioritise local services (to serve Dawlish, Teignmouth, Newton Abbot, Torbay and Totnes) through the periods of disruption which are likely to take place over many years and divert some services to/from Plymouth and Cornwall over the northern route. This means taking a strategic view of the network and it means progressing the Tavistock-Okehampton scheme as a twin priority alongside work on the coastal route.

The risks around developing branch line services for Okehampton and Tavistock

Devon County Council is right to press for the re-instatement of services for the two towns. But there are two problems it faces, as a recent report on rail re-openings has highlighted:

“The objective of Government policy regarding new rail lines has been twofold. First, schemes must pass a high bar of financial sustainability with predicted revenue from fares underwritten by the scheme sponsor. This reflects the wider Government objective of increasing the proportion of railway costs borne directly by passengers. Second, while identifying the benefits that can come from reopening rail lines, Ministers have repeatedly made clear that identifying and promoting reopening projects is a local issue.” See Campaign for Better Transport: The case for expanding the rail network, February 2019

In effect Government policy doesn’t support rail re-openings that increase operating subsidy, and to avoid this outcome it expects local authorities (or other stakeholders) to under-write passenger revenues. Were local and regional agencies suitably funded, this would make sense, ensuring funding decisions taken locally showed suitable fiscal prudence. But of course such agencies are not suitably funded.

The idea of re-opening local services to Tavistock and separately to Okehampton has been around for decades. It is an approach that avoids the twin challenges of property purchase which will be needed to re-instate the line across Tavistock and the need to ensure that Meldon Viaduct can be made secure for renewed service. Even so, progress is painfully slow. There are two real risks which in part explain why progress to date has been so slow:

- These schemes, despite goodwill and lots of support, fail to come to fruition because while the investment costs are relatively low, neither service, each operated as a branch line, has any chance of breaking even (revenues covering operating costs). On the other hand, re-creating the through route brings much higher revenues, and through train operation delivers operating cost efficiencies. Specifically, a through route:

- triples the number of key station-station flows and has a similarly uplifting impact on revenues

- allows for valuable through train operations – for instance to Exeter city centre and onwards to Waterloo, which again makes for efficient train fleet operations while adding hugely to revenues

- The way in which the two separate railways would be created, to branch line standards, will make it difficult to complete the line and operate it to main line standards at a later stage. Specifically, in Tavistock, a station would be built at the outer edge of the town, but it would need to be replaced (i.e. closed) when a station is re-established close to the town centre when the through line is re-established. Closing stations is not only unpopular, it’s also (intentionally) very difficult to achieve. A town the size of Tavistock cannot support two railway stations (and the same is true for Okehampton).

What should be done next?

After a decade-long gestation period, the first of four portions of the major housing development at Callington Road, Tavistock was given the go-ahead (on ‘reserved matters’) last month. Ultimately, Bovis Homes will build over 750 homes on the site. The planning agreement stipulates that the developer will make a contribution of £1.53m towards railway infrastructure for every 100 homes built. But as we noted above, the idea of a station on the South West edge of Tavistock is a poor choice and makes the challenge of creating a through route harder, not easier.

Local opinion is not supportive of the housing expansion, but it is supportive of a re-instated rail service, as our research in 2015 discovered. The £11.5m+ developer contribution to rail will be payable in instalments and it will not meet the costs of line re-instatement from Bere Alston. And – as explained above – it appears unlikely that Devon County Council would be able to underwrite the limited revenues that would flow from a single new station on the SW edge of the town (as well as funding the balancing part of capital outlay needed).

It is time for some realism. What’s needed is recognition from central Government that recreating the Okehampton-Tavistock line is not just a regional priority but a national priority. People ask for action on climate change, and here is a project that provides a response to the risk of the South West being cut off from the national rail network because of sea level rises happening now.

It is a project that will also bring widespread benefits to an area with very poor accessibility to jobs and higher education & training opportunities. Devon County Council should kick-start the process by allocating the first part of the housing developer’s contribution to railway infrastructure at Tavistock to the detailed feasibility studies that are needed.