Reconnecting communities to the national rail network by restoring closed branch railway lines is popular, with many applications to the Department for Transport’s Restore Your Railway fund. Government announced the first go-ahead on 19 March 2021 which should lead to regular services from Exeter to Okehampton later this year (ref 1).

But are there lines of regional or even national – as well as local – significance that also should be brought back into use? Main lines instead of branch lines?

In “Disconnected: Broken Links in Britain’s Rail Policy” (ref 2) authors Chris Austin and Richard Faulkner devote a chapter to this question when they looked at missing main lines

Austin and Faulkner on lost Main Lines

Alongside various local lines that have been lost, their book covered five main lines that have been closed in the last 60 years. Maybe other strategic routes such as the East Lincolnshire Line which connected Grimsby, Louth and Boston with services to London should have qualified as a main line too. We have certainly advocated its re-instatement elsewhere (ref 3).

The longest of the selected five main lines is the Great Central – although its suburban route from Aylesbury into its London terminus at Marylebone remains in use today. While serving a string of cities through the East Midlands and onwards to Yorkshire, the Great Central largely duplicated a rival railway company’s service offering. The authors conclude that the biggest loss from closing the Great Central main line from the north side of the Chilterns is capacity. Interestingly, this is the same corridor served by the eastern arm of HS2, although by missing the cities the Great Central served, this part of HS2 has minimal released capacity benefit (ref 4).

The most northerly main line loss is the Caledonian Railway from Perth to Aberdeen along Strathmore, serving intermediate towns such as Forfar. This route was superseded as long ago as the 19th century when completion of the Forth and Tay bridges created a more useful route to Aberdeen via Dundee. Authors Austin and Faulkner conclude that when the Caledonian line closed, the greatest loss was rail connectivity to the small intermediate towns it served along Strathmore. They conclude simply: ‘it would be hard to argue for the restoration of the line today’.

Three missing main lines that could be re-opened

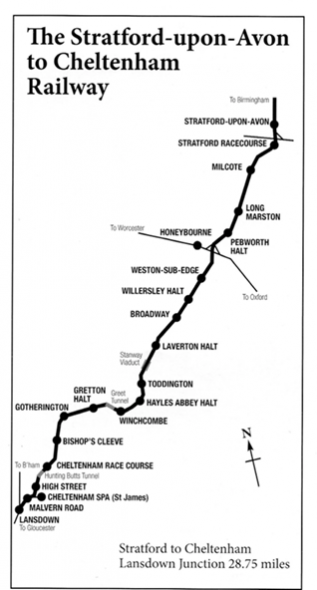

The first of these is the line from Stratford upon Avon to Cheltenham via Honeybourne. The report authors say that the loss of this connection as a useful diversionary route is a critical factor in the case for its re-instatement. We agree. And alongside linkages between Oxford and Stratford upon Avon (of great value to tourism flows), there is the ability to re-create a linkage from Cheltenham to Stratford and on into Birmingham’s Moor Street – which is set to become a new rail hub, alongside Curzon Street HS2 station.

Much of the line exists today as a heritage line, and applications have been made to the DfT ‘Restore Your Railway’ fund to re-open the line in stages.

Besides new passenger services, it could provide a useful freight route including for intermodal traffic between national distribution centres in the Midlands (for example, at Daventry and East Midlands Airport) and South Wales (and the South West in due course), overcoming network limitations in the Birmingham and Bromsgrove areas.

As is often the case with such schemes, the biggest problems arise in urban areas. The route southwards from Stratford-upon-Avon station remains unhindered by property development but would need major highway bridging work. The route northwards across Cheltenham is now a valued walk/cycle-way and is regarded by report authors Austin and Faulkner as in effect lost for re-use as a railway. A short new connection across open country north of Cheltenham is more likely be an acceptable approach.

The second is the Oxford-Cambridge line, closed in 1970. It has already been partly restored and a company, East West Rail (EWR) established, with full Government support and funding. It serves places of considerable prosperity and growth potential, including the two university cities at either end of the route and Milton Keynes.

It has from time to time been suggested that this line, which crosses the route of HS2 near Claydon in rural Buckinghamshire should be the site of a new interchange station between EWR and HS2. While superficially attractive, this makes little sense. Besides the problem of introducing a station call on a 360km/h section of HS2, it would create a point of maximum accessibility and place huge development pressure in a part of deep rural England. This very prospect was in fact examined by the consultants who carried out the early studies into north-south high-speed rail in 2000-1 (ref 5). Development at this location at the time was seen to be completely incompatible with local and regional spatial development plans.

There are other key intersections between the east-west Oxford-Cambridge railway and north-south main lines that should be exploited. One of these is at Bletchley/Milton Keynes on the West Coast Main Line (WCML). Services into Milton Keyes from EWR need to operate over the WCML from Bletchley. HS2 will remove fast non-stopping services from the WCML and a major timetabling restructuring will take place. It is to be hoped that this will facilitate the creation of direct Oxford-Milton Keynes rail services in due course.

The final main line closure considered by authors Austin and Faulkner is the route from Exeter to Plymouth via Okehampton and Tavistock. Today the only line between Exeter and Plymouth (and, indeed, Cornwall) is Brunel’s line – distinctly not his finest:

“a difficult section of railway, with steep gradients between Newton Abbot and Plymouth over the notorious South Devon banks and there is a vulnerable coastal stretch of line”.

The vulnerable coastal route between Teignmouth and Dawlish

Photo: Greengauge 21

The authors continue:

“the line has been closed on 19 occasions, varying from part of a day to eight weeks. The average closure periods for interruptions is six days”.

The link between Okehampton and Bere Alston closed in 1968. The line from Exeter to Okehampton was not listed by Beeching for closure and has remained open, although with minimal use (and maintenance) in recent years. This route has just been announced for ‘re-opening’, and over £40m is being spent to bring track and signalling up to scratch.

But the big prize is re-creating a through route again, filling in the 15 mile gap between Tavistock and Meldon. On this prospect, Austin and Faulkner conclude as follows:

“If the line […] were restored, it would provide an additional route between Exeter and Plymouth, improve rail access for West Devon and provide a closer railhead for North Cornwall.”

“However, decisions are never straightforward… Re-signalling the whole route from Crediton to St. Budeaux would be required… The first part of the route [the existing Exeter-Barnstaple line]… is in the flood plain”

“Clearly the first priority is to protect the existing [coastal] route… However, the added value of the Okehampton route is clear and had it not closed, it would today be both a valuable line of regional significance serving areas of Devon and Cornwall that are remote from a railhead. With rising sea levels, and the need for higher levels of maintenance of the coastal route, it would also have clear added value as a diversionary route”.

“Apart from that, Plymouth with its population of a quarter of a million is the only city of that size with just a single rail line with the rest of the country. In 1968 that was not seen as an issue. In 2015, it is, and second line is needed, not just because of the vulnerability of the single route at Dawlish, but because from time to time it will be closed as a result of failure or incident, and quite frequently for maintenance. Something better than the present arrangement is needed for the 21st century.”

Conclusions

Of the five main lines examined for re-opening, the biggest (the Great Central Railway) could not be re-created today through the cities of Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield without very costly and disruptive works. But its modern equivalent – HS2 – is a viable successor, although its route between the East Midlands and Yorkshire needs to be reviewed. Either way, this will provide the eastern side of the country with a new high-speed route into London: something that the Great Central always lacked.

The loss of the Caledonian main line from Perth to Aberdeen is no doubt regretted by many, but its re-instatement would bring only local benefits.

The three remaining lines have full re-opening plans. These are not exercises in nostalgia. Their common feature is that they each perform wider strategic roles, as well as bringing local area benefits. East West Rail is leading the pack, having gained Government support after strong campaigning. Its full cost has been estimated at £5bn (2019 prices).

South West England

The campaign to re-create the ‘northern’ route between Exeter and Plymouth is compelling (ref 6). Even since 2015, when Austin and Faulkner spoke about addressing the challenges on the existing coastal line, awareness of the significance of sea level rises on the coastal route has grown. Northern route re-instatement costs were estimated in 2014 at £875m for a railway designed to intercity standards and with measures to protect the initial part of the route west from Exeter (shared with the Barnstaple line) from flood risk.

Disused track alignments near Brentor

Photo: Greengauge 21

Just like East West Rail, the second main line between Exeter and Plymouth offers substantial connectivity gains across a wide geography. But it also provides a unique network resilience bonus.

Unlike the Oxford-Cambridge arc, Devon and Cornwall are not areas of high prosperity. The adoption of this west country scheme by Government, and the allocation of proper funding to it, is a real test of Government’s commitment to levelling up parts of the country doing least well economically.

Half of England’s most deprived areas lost their railway stations in the Beeching cuts, a new report has found. Research by Campaign for Better Transport found that 88 of 175 stations in the poorest areas of the country have closed since 1960, with 23 areas losing two or more (ref 7). Many of these areas are in the North of England, but the local authority with the overall lowest level of productivity/head (income and profits) is in the West Country: Cornwall. Its rail connectivity depends on a single, vulnerable, line along the south Devon coast being kept open.

As we have seen, East West Rail and Stratford-Cheltenham main line re-instatements both have some relevance to a wider aim of getting the most from HS2 investment.

Exeter-Okehampton-Tavistock-Plymouth provides long term assurance in dealing with perhaps the most pressing case of a global warming threat facing the national rail network.

One more missing link

Whereas it could be said that HS2’s Eastern Arm is a modern version of the northern part of the (lost) Great Central Main Line, in practice an even more significant main line loss could be the North Midland Line which linked South and West Yorkshire (Sheffield-Rotherham-Normanton-Leeds).

Source: Flickr

This line was overlooked in the Austin-Faulkner book, and is now substantially built over, making its re-instatement all but impossible. The ambition for a better and faster link between Sheffield and Leeds – and better connections to the key places between them (notably Barnsley and Wakefield) – remains. The corridor is relevant to both Northern Powerhouse Rail and HS2, but a firm plan that can be prioritised is not yet apparent. Yet here there is a strong case for new, electrified, rail capacity, able to overcome slow journey times and network congestion. Sometimes rather than re-instatement, new build can be a better approach.

Greengauge 21

April 2021

Ref 1: Greengauge 21 provided technical support to the relevant train operating company, GWR, examining the wider social benefit from a restored railway for the Okehampton catchment area

Ref 2: Published by OPC, 2015. ISBN 978 0 86093 664 0

Ref 3: http://www.greengauge21.net/challenging-region-inequalities-the-transport-element/

Ref 4: http://www.greengauge21.net/rail-investment-for-the-north-midlands-how-to-make-it-happen/

Ref 5: WS Atkins et al report to Strategic Rail Authority, 2001

Ref 6: See https://northernrouteworkinggroup.wordpress.com/

Ref 7: Daily Telegraph, 1st April 2021